Matthew Leitch, educator, consultant, researcher

Real Economics and sustainability

Psychology and science generally

OTHER MATERIALWorking In Uncertainty

Chairing meetings

Contents |

Many people involved with risk management and internal control are interested in integrating risk management into core management activities and in promoting a good ‘culture’ within which risk is managed well. This article looks at the crucial task of doing those things within business meetings.

The suggestions are made as a series of tactics to be used by anyone chairing a meeting, anyone temporarily in control of a meeting, or indeed anyone frustrated by a disorganized and unproductive meeting who would like to influence their colleagues positively.

The overall aim is to promote meetings that are fair and thoughtful, and where participants demonstrate wisdom and expertise. At the same time, selfish, unfair, lazy behaviour is to be minimized. This is likely to give better, fairer results and to be less stressful and tiring for meeting participants. Although you will probably spend more time thinking about what matters you will spend less time thinking about conflict and irrelevances.

Tactics to initiate good meeting behaviour

It is easier to manage a meeting if you start the meeting and sections of it in the right way. Here are some tactics for doing that.

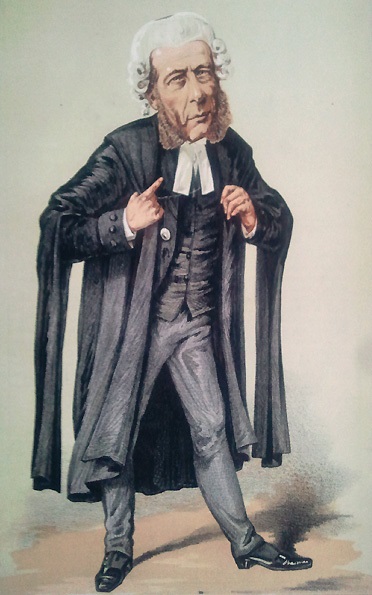

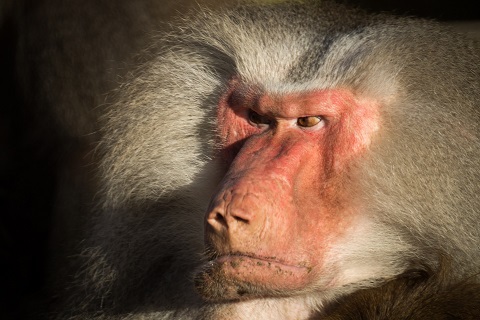

Manage primate politics

Imagine a naturalist, more used to observing troops of baboons, describing a typical business meeting. ‘Now the younger male challenges the dominant male, squaring up to him with a challenge to his ideas for a new policy on photocopier use.’ A minute later the naturalist might say ‘The younger male now shows submissive behaviour, baring his teeth fully, backing away, and flattering the dominant male's choice of policy wording.’ That's us.

Beneath the civilized, intellectual level of business meetings there is another level of meaningful interaction. Sometimes this ‘primate politics’ level is the main driver of a conversation, with rivalry, alliances, and (re)building relationships being the main reasons that anyone speaks at all. At other times primate politics are almost forgotten and humans reach unusual heights of thinking, free from worries about personal relationship and reputation management.

It is easier to have a good meeting in which management is done well and risk is managed if we can reduce the intensity and influence of primate politics. Some basic steps are these:

Highlight a common enemy: The common enemy might be another company, a regulator, another group in the same organization, or simply the tough task the meeting is to tackle. When introducing the meeting, or a task within it, mention the challenge or the competition and encourage people in the meeting to feel that they need to work together to overcome it. This channels primate politics usefully. For example, in ordinary times a very capable colleague is a rival, but in a crisis that colleague becomes a valuable ally.

Make the meeting the group: Create a sense that the people in the meeting form a group that is to work together. Other groups that people may be part of are less important for the time being. The meeting forms a group where the culture is one of thoughtfulness, objectivity, and so on, and where value is assessed on the basis of the quality of contributions made.

Highlight personal interests: It is well understood that in some situations it is important to declare personal interests. The chairperson can use this principle to reduce primate politics. By making motives explicit the chairperson puts everyone on alert.

Prime good behaviour

Most people understand that a fair, thoughtful, rational meeting is a good thing but they still behave better if they are reminded of that. Research by Dan Ariely and Keith Stanovich shows that timely reminders are among the most powerful things that can be done to promote honest, rational behaviour. Here are some examples of phrases that can be used:

‘This is a sensitive subject so let's make sure we discuss it objectively and fairly.’

‘I know we have a lot on the agenda today so please stay on topic, but let's make sure we are always patient and give these topics the careful consideration they require.’

‘Obviously there's a lot we don't understand yet about this problem so we need to be especially aware of the limitations of our knowledge.’

‘Our last meeting was an excellent demonstration of thoughtfulness and teamwork. Let's try to do the same again today, or better.’

‘We've talked before about the importance of taking a structured approach to this planning task, being open minded, and carefully considering each option. Let's do that now.’

Outline an approach to each task

Meeting agendas usually have several items on them and the items are of different types. For example, one item might be an update that just requires people to understand the information offered, while the next may be a difficult choice between three options, and the item after that could be a tricky problem that currently has no candidate solutions.

To help people tackle each task rationally, identify the type of task and outline a suitable approach to it. Here are some examples:

‘Our next task is to decide whether to accept or reject the offer received last week. Can we start by just checking who here has already studied this offer and then we can perhaps have a briefing from one of the experts if necessary before considering the consequences of acceptance and rejection.’

‘Now we are going to hear from Jill, who was at the Level 2 briefing yesterday and will let us know what she learned. Jill has a presentation for us so please store up your questions for the end to make sure you understand exactly what she means.’

‘Turning to the long-standing problem of absenteeism, the figures for last month are again disappointing and so our next agenda item is to think again about the causes and control of absenteeism. To start us off I'll ask Peter to recount the story so far, including what we have imagined the issues to be, what has been done to reduce absences, and what we know and don't know about the results of those changes. I'll then invite any contributions of facts, insights, potential solutions – any ideas at all that might be helpful. Let's try to think open-mindedly about this and focus on specific facts rather than generalizations.’

Prepare contributors who lead an item

Often an agenda item will be led by someone who is not the chair. For example, someone will have an update on something they are the expert on, or will have a proposal for consideration. The tactics of priming good behaviour and outlining an approach to the task can be used through that person if some preparation is done. In some cases it may be possible to lay down some standards for commonly occurring items, such as requests for investment approval and presentations of recent financial results.

Highlight and outline digressions

Having initiated a discussion with a rational outline of an approach, the chairperson will often find that the discussion goes off on a justified digression. For example, the chairperson might have suggested an outline approach thinking that a particular decision has already been made and now the task is to work out how best to live with it, yet within a few minutes it emerges that the decision has not been made at all.

At this point the chairperson should point out what has happened and provide a new outline approach for the next part of the discussion.

Push for consideration of all relevant, legitimate interests

The chairperson should try to keep track of which interests have been considered and prompt the group to cover all relevant, legitimate interests. For example, if this year's profit has been discussed in detail as a consideration shaping a business plan but nothing has been said about longer term results, non-financial results, the interests of employees, or impact on society and the planet then the chairperson should prompt consideration of these other interests.

Put the spotlight on limited knowledge, control, and resulting uncertainty

Our knowledge and control are usually limited, and that leaves us uncertain about the future, the past, and the present. Nearly all management tasks involve this uncertainty but humans have a tendency to overestimate their ability to predict and control the future. Countering this tendency is a vital job for the chairperson. The chair should identify the inevitable areas of uncertainty, put attention on them, and give people permission to be unsure. Here are some examples:

‘Somehow, at about half past ten on Saturday night, over 10,000 incorrect invoices were sent out automatically by our billing system. This has only just come to light and obviously I don't expect a full analysis of the issue and its various causes right now. But what do we know so far?’

‘We've come up with several potential names for the new product and at this point it is not reasonable to imagine that we can choose the best without some research.’

‘We need to evaluate the performance and potential of each member of our sales team. Of course past sales figures are persuasive but let's remember that skill and effort are not the only drivers of sales. Luck and a good sales territory are also important. We need to pull together all the information we have to make some tentative estimates of performance and potential. Two members of the team have only been with us for a month so we need to be particularly aware of our lack of information about them.’

‘As we all know, estimates like this can be very tricky and some quite subtle factors can make big differences to the long term results. We still need to think about the consequences of our decision but we need to be clear about the limitations of our understanding and willing to do a bit more study if that seems worthwhile.’

Summarize and reset

Once the group has made some progress on an item the chairperson can summarize that in a way that helps clarify what has been achieved and again outline the next steps. It is helpful if the summary again highlights the underlying logical structure of the task and the options under consideration. Here are some examples:

Diagnosis: ‘OK, so we have been trying to diagnose the problem with the RT5000 machine and so far we have three hypotheses. One is that the reserve tank has leaked and oil is clogging the ventilator, leading to overheating and automatic shut down. Another hypothesis is that the ventilator power supply has failed, again leading to overheating. The third hypothesis is that some gunge has gone into the main chamber causing friction and overheating. We know that there has been overheating but don't yet know how best to narrow down the cause. Let's now consider ways to get more information that will help us with this diagnosis.’

Problem solving: ‘We have a problem with the interface between the embedded software and the network. At the moment we can't think of any way to get the two talking to each other because of the lack of synchronization. Let's now think more widely about other interfacing principles that we might use.’

Design: ‘So, in summary, we have two leading ideas for the overall floor plan. One is the L shaped layout and the other is the H shaped layout. We've done a preliminary assessment of each, just looking at cost and total usable space. Let's now consider some other factors before we decide whether to continue developing both ideas or just focus on one.’

Planning: ‘Thank you everyone. So we started with the idea of a three phase structure, with the peak effort in September, but seeing the staffing problems this would probably cause we are now looking at a revised plan where the peak effort is brought forward to July and the first two “phases” become parallel activities. After our break I'll ask you to consider this alternative plan on a number of other criteria, including the customer's potential reactions.’

Poll secretly

Collective wisdom can be powerful, but only if each person's thinking is tapped independently. To stop people reacting to each other's opinions instead of giving their honest view, try tactics like these:

‘It would be helpful to get a sense of our views at this stage. Can I just ask you all to write down, now, your preference between the three options we've been looking at. When we have all done that I'll go round the room and ask you to tell me what you have written down.’

‘Who has an opinion on this? Don't tell me now. Just write it down and then we'll go around and you can tell me what you've written.’

‘We have to estimate the number of jelly beans in this jar. Please take a look and write down your estimate on these slips of paper. Do not discuss it with anyone else or try to see what others have estimated. When you're done give me your slip and I'll work out an average.’

‘How much do you think we should have as our maximum bid? Please write down your answer on these slips of paper and give them to me.’

Secret polls like this avoid a problem called anchoring. The anchoring effect is our tendency to make estimates close to a number someone else has just mentioned. If the first person you ask says ‘20,000 jelly beans’ then that will tend to encourage everyone who hears that and then makes an estimate to give higher estimates than they would otherwise, even if 20,000 jelly beans is obviously too high. It is best to ask for independent estimates then take the average.

Establish ground rules that exclude advocacy

If circumstances permit, it may be possible to establish some formal rules about meeting behaviour. These will probably include some obvious points that don't really need to be included, like helping to keep to time and being polite, but should also include rules that are more restrictive than we are used to.

In particular, the ground rules should exclude advocacy.

Advocacy is one of the most damaging but familiar bad behaviours that occurs in meetings. It is where people start to argue for their position and act like politicians in the House of Commons or barristers in a courtroom, saying whatever they think they can get away with to win the argument. When advocacy takes over, fairness and rationality are lost, which is a sad comment on politics and the law.

Recognizing advocacy takes a bit of skill and not everyone can do it. The main indicator of advocacy is the use of tactics other than logic and evidence, such as emotive language, trick arguments, and strong framing.

Behaviours that do not reliably indicate advocacy include having lots of arguments in favour of a position, not knowing any genuine counter-arguments, taking a more extreme position than other people, and not being willing to listen to counter-arguments. For example, you know that in the usual notation of arithmetic and with decimal numbers, 2 + 2 = 4. If you cannot think of a counter-argument to that and do not want to listen to counter-arguments that does not make you a dogmatic, narrow-minded advocate.

In contrast, the following statements, tricks, and mistakes are indicators of advocacy:

Failing to accept a clear and correct line of reasoning that contradicts the advocate's position. This is usually done by shifting to a new topic without responding to the damaging line of reasoning.

Avoiding discussion of evidence or considerations that weaken the advocate's position.

Countering with a long list of questions asking for clarification, including clarification of points that are obvious by implication and do not need clarification.

Heavy reliance on arguing that others agree or an authority agrees.

Emotive language, e.g. ‘To refuse this offer would be crazy at this time.’

Irrelevant comparisons, e.g. ‘I know these results are bad but they could be worse.’, ‘Doing this is better than doing nothing.’ (said when the alternative is another action, not doing nothing).

Witty but irrelevant or misguided quotes from famous people, perhaps humorous.

Irrelevant arguments by analogy, e.g. ‘Just as the leopard cannot change his spots, so we cannot hope to ...’

Using convenient but unconvincing correlations, e.g. ‘A study showed that people who eat more chocolate have a lower Body Mass Index, showing that eating chocolate helps you slim.’ (or perhaps fat people say they stay off chocolate).

Making illogical arguments confidently and sticking to them with the same confident manner when the flaw is pointed out.

Using words that imply another person's facts and logic are just their opinion or point of view.

Claiming that another person's lack of some particular experiences means they are not qualified to comment on something, even though the comment they have made does not need any experience to back it up (e.g. it is based on logic or survey evidence).

Denigrating intellectual ability, scientific method, or technical knowledge, e.g. ‘Let's not get into nerdy detail like that.’ and ‘Well, I may not have Phd in statistics, but I do know that I had a cup of that herbal remedy and it worked for me.’

Complaining that critics are ‘negative’ thinkers, unhelpful, and not team players.

This is far from a complete list but you get the picture. Dishonest ploys are a sign of advocacy and should trigger action by the chairperson. But, what can be done?

It is difficult to tackle advocacy for a number of reasons. It is not always recognizable instantly (so you can't just block it) and people in advocacy mode are often argumentative and unreasonable. They may have used tactics to get the group to side with them that also undermine the position of the chairperson. One great difficulty is that we usually tolerate this kind of trickery without comment, even though most of us sense the unfairness and feel stressed and annoyed by it. That is a reason why having formal ground rules banning advocacy can be helpful to the chairperson.

The ground rules should briefly explain what advocacy is and give permission for the chairperson and other participants to point out trick arguments and advocacy when they occur.

Select meeting participants who can be relied on to contribute well

Just occasionally it may be possible to select meeting participants who will make it easier for the chairperson to run a good meeting. Perhaps you have to have someone representing a particular group, but does it have to be that person?

Tackle difficult participants privately

In some situations the chairperson is in a position to talk to participants in a regular meeting privately and ask them to change their ways. If you have been forced to intervene several times to stop someone who keeps behaving as an advocate, or because someone keeps making long statements that make no sense, then something has to be done. It is better to bravely face the person as an individual than suggest more ground rules, which will annoy everyone except the person you are trying to reform.

Tactics for responding to good and bad behaviour

In addition to setting up a good framework for a meeting, the chairperson can influence proceedings by responding well during meetings to behaviour when it occurs. Here are some tactics for doing that.

Reward good behaviour

Having primed good behaviour and outlined a rational approach to each task the next step is to show some appreciation when people respond appropriately. For example:

‘Thanks Tracy, for that very clear explanation of the main options.’

‘That was an excellent analysis and I'm sure we all appreciated your careful explanation of the different types of evidence available to help us assess this product.’

‘Paul, I know you've put a lot of effort into developing this plan so I really admired the objective way you presented the evidence to date on its likely results. You're right that a lot depends on the performance of the core technology and that we can't know more about this until the field trials are substantially complete. I would like to take up your suggestion that we discuss ways to increase flexibility in the plan.’

‘Lesley, thanks for highlighting a source of evidence that we seem to have overlooked until now. That was really useful.’

Identify uncertainty beneath disagreements

People in meetings often spend a lot of time trying to reach ‘consensus’ but too often this ends with people compromising and ending an argument just to escape a stalemate. A better approach is usually to recognize that disagreement is often a sign of uncertainty. When two people disagree it often means that neither really knows. The chairperson can point that out, suggest actions to resolve the uncertainty, and move the meeting on. For example:

‘That's enough on this point. How much do we really know about what nineteen year olds think about our privacy policy without testing? I suggest you two organize a quick poll to find out and report back next week.’

‘This has been an interesting discussion but before we get mired in advocacy I suggest we recognize that this disagreement indicates uncertainty. We don't really know what this new development means and we won't resolve this by just sitting here and talking. Does anyone have any suggestions as to how we can resolve our basic uncertainty over who leaked the information and why?’

‘The results of our secret poll are an average of £21,000 but the spread is from a loss of £12,000 to a profit of £300,000. What I get from this is that we don't really know. Let's take another look at the plan and see if we can improve its flexibility.’

Respond to unhelpful primate politics

Not all primate politics are unhelpful. As suggested earlier, they can be channelled to encourage teamwork. Also, if for some reason a relationship has been damaged during a meeting, it is usually a good idea to let people spend some time on smoothing things over by running through areas of agreement, making apologies, flattery, and explaining away ‘misunderstandings’. However, primate politics can also be damaging. Trying to maintain relationships by reaching compromises sometimes leads to agreements that are illogical and will not work for anyone.

Here are some things the chairperson can do to respond to primate politics during a meeting:

Block silly compromises: The chairperson should be suspicious of any compromise, especially if feelings have been high, and should try to prevent illogical compromises being reached. It is better to agree that no agreement has yet been made than to agree to something stupid.

Continue to keep all stakeholders under consideration: The chairperson's reminders to consider all legitimate interests of stakeholders, to consider more alternative approaches, and to use all evidence, will tend to counter primate politics, which often amount to wrestling over whose interests are most important.

Separate ideas from individuals: Write ideas on a whiteboard with a name of their own. Avoid reminding people who suggested each idea. Get individuals to suggest more than one way forward. Ask everyone for evidence. For example, if John thinks astrology works and Julie thinks it's bunkum then call those ideas the ‘Astrology Works hypothesis’ and the ‘Astrology Does Not Work hypothesis’ and, if it matters to your meeting, ask everyone what evidence they are aware of that will help to get to the truth. This is different from asking John to give his reasons for his belief and then asking Julie for hers.

Respond to advocacy

Advocacy is a major threat to good management and to risk management specifically and when it happens it should be responded to by the chairperson. The chairperson can interrupt while the ploy is being used or when the advocate finishes speaking. Here are some tactics that can be used once interruption has occurred.

Hold to the point: When someone dodges a damaging point by switching the topic or simply repeating their position the chairperson can say ‘Let's just stay on the point that was made and make sure we fully understand its implications. Wendy just pointed out that ...’

Move on: The chairperson who spots a ploy quickly can interrupt it with something like ‘Thank you Julia, but let's just move on shall we.’

Redirect towards facts and logic: e.g. ‘Thank you Paul, but can you just focus on giving us the facts please.’

Point out irrelevance: e.g. ‘That comparison isn't relevant because the alternative is not doing nothing. An alternative response has been proposed, which is to ...’

Protecting a speaker: A common tactic, especially when there is a group of advocates arguing for a position, is to stop others from talking or from completing points by interrupting them with objections or by firing a series of questions or points at them without giving them a chance to reply. The chairperson can stop these behaviours and insist that people are given a fair chance to speak, to complete their points, and to respond to questions and points made. The chairperson can also interrupt a long series of points or questions and ask that they be put one at a time, so that each can be considered properly.

Highlight hints: Emotive language often amounts to hinting at something without actually claiming it, and this is done to avoid having to justify the hinted point. For example, if some technology is referred to as ‘bleeding edge’ by someone who does not want the company to use it, the chairperson might say ‘When you say “bleeding edge” are you saying that this is technology that is both new and potentially dangerous?’

Disregard that: e.g. ‘Ladies and gentlemen, Gary has just made a joke about mathematicians having no social skills. It's not relevant to the value of the model outputs we are looking at and I ask you to disregard the joke and the implied slur on the people who built this model for us.’

Point out rule infringement: e.g. ‘Our ground rules ban advocacy, and you have just spent quite a long time giving us the harrowing details of one particularly serious case when what we need is to understand the total scale of the problem.’

Point out the trick: e.g. ‘Bob, you just characterized Paul's position inaccurately then criticized it on grounds that rested on your misrepresentation. This is the second time you have done that in this meeting.’

Point out the trick and say why it is not acceptable: e.g. ‘Prunella, you just described the failures as “repeated” but I see from the file that in fact there were two failures. It's slightly misleading to say “repeated” in this context so please state the number of failures instead.’

When someone is in advocate mode and is challenged over their use of an unfair trick their first response will often be denial. They will say their language was not emotive, or that they were making a legitimate point, or try to wriggle off the hook in some other way. Sometimes they will be right.

The chairperson's problem is that it can be difficult to be sure that someone is behaving badly. However, there is no need to intervene over every infringement. Just picking off the most blatant tricks will be a giant step forward. Over time, the persistent offenders will become clear and their favourite ploys will become familiar. The chairperson's confidence will grow along with their ability to intervene.

Clarify or block unclear or confused contributions

Most meetings are challenged by a lot of uncertainty so it's not helpful to have people making statements whose meaning is unclear. Unfortunately, some participants make contributions that are persistently unclear or confused. Asking them to be clearer tends to trigger an even longer and less meaningful speech, so it is better to ask the speaker to restate their point in fewer words.

Is it rude to ask for this kind of clarity? No, not if their contributions are genuinely unclear or confused. It is worse to leave everyone else sitting through long, useless contributions, straining to discern meaning.

How far can you go?

If all the suggestions above were put into practice immediately the result would be ugly, with meeting participants probably complaining that the chairperson has become a tyrant. This is despite the fact that few people would disagree with the overall intention or any of the methods. What they will not enjoy is having all their bad behaviour pointed out.

However, a high standard of behaviour can still be achieved by intervening from time to time and continuing the pressure over a series of meetings. Gradually, as people learn to behave better, the chairperson will be able to run a great meeting without saying much more than usual.

Made in England